THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

Riversides and Seafronts

One of the oldest riverside promenades is that of the Cascine, in Florence. This is the model on which was based the promenade that Marie de’ Medici, daughter of the Grand Duke of Tuscany Francesco I de’ Medici and wife of King Henry IV of France, built along the Seine around 1616 and that would later become known as the Cours la Reine.

The English traveller Moryson described it in 1594 as ‘the most sweete walke that ever I beheld. It hath in bredth some five rowes of trees, on each side, and a like distance of greene grasse betweene those trees, but it reacheth in length many miles; and out of the River Arno are drawne two ditches, which runne all the length of it, one upon each side’.

The Cascine remained a distinguished and frequented summer promenade throughout the following centuries. The American painter Rembrandt Peale visited it in July 1829 and wrote: ‘The fashionable place of resort, especially for the equipages of the Florentine and English nobility, is on the grounds laid out for a promenade, both for walking and riding’.

Florence. The Cascine Promenade. Queen's Avenue,

postcard, late 19th century.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

“Taking the fresco” assumed a very peculiar aquatic meaning in the case of Venice, where the local dialect term fresco designated the assembly of many gondolas and small boats rowed up and down the Grand Canal. At the end of the 17th century, the secretary of the French ambassador in Venice de Saint-Didier described the impressive sight of three to four hundred gondolas travelling back and forth on a stretch of the Grand Canal near the Church of San Geremia and praised the gondoliers for their rowing skill.

was also performed on Ascension Day, Corpus Christi Day, the Festa del Redentore—on which it still enjoys considerable popularity—and other religious and lay events. In many of these cases, the fresco promenades used the same water routes traditionally taken by the boat races, thus following a historical pattern analogous to those of the urban corso promenades and horse races.

The Noble Race [Corso] from San Stae to the Croce, Gabriel Bella, 1779?,

Venice, Querini Stampalia Foundation.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

In some exceptional and amazing cases, the association between water and summer promenade was created artificially.

This occurred in 19th-century Siena, where the Piazza del Campo was flooded with the water of the Fonte Gaia to allow a double promenade: in small boats at the centre of the square, and by coach around the outsides.

In 17th-century Rome, fountains and water games were introduced in Piazza Navona, which was sometimes also partly enclosed and water-filled for the pleasure of the promenaders who visited it on foot and by coach in the summer heat.

Piazza Navona Flooded, Antonio Joli (1700-1777), private collection.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

Italian coastal cities usually held their summer promenades along the seafront.

The Passeggiata della Marina in Palermo was established in the late 18th century and ran between Porta San Felice and the botanical garden dubbed ‘La Flora’. The promenade was a key high-society summer event, which Vivant Denon described in 1778 as a ‘charming promenade along the seafront, a rendezvous for the whole of Palermo, in which one can walk in the shade and in the fresh air after six o’clock. No one goes to sleep without taking a stroll on the Marina’.

On 4th November 1824, Trieste inaugurated the coastal promenade of San Andrea between the city centre and the nearby Servola. In the 18th century, Genoa held its summer promenade along the high stone wall that bounded the harbour, while in the following century the summer promenade for those who kept carriages took place every evening from the new Mole to the Acquasola. The promenade in Ancona was described as ‘pleasant’ as early as 1594, and in the 19th century Coxe noted that: ‘The inhabitants of Ancona are fond of the promenade, and are generally seen in groupes, in the evening, on the Mole’.

The Marina of Palermo, Illustrated Times, 1860.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

Also in 18th-and 19th-century Naples, the Molo Grande (Great Pier) was a fashionable summer promenade for city dwellers and Grand Tour travellers, who had the opportunity to enjoy not only the fresh air, but also its lively atmosphere.

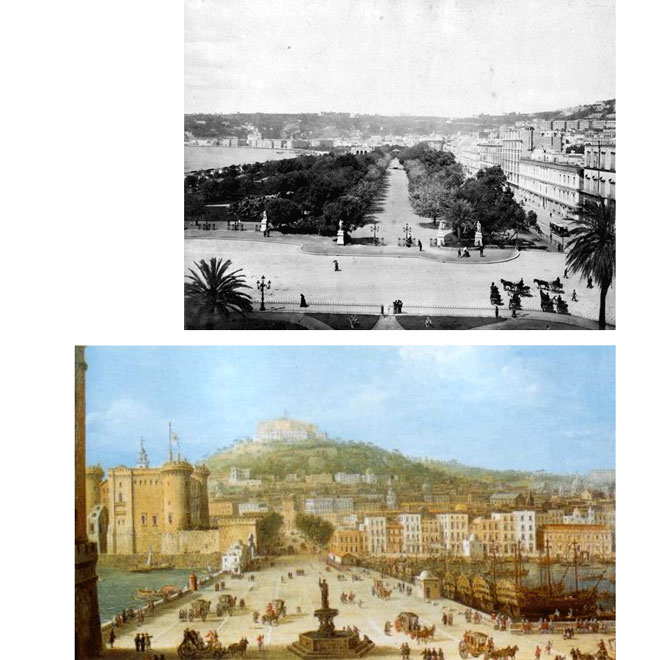

From the late 18th century, Naples also had the Chiaia promenade, which combined the pleasures of the gardens of the Villa Reale and the seaside. With its five tree-lined alleys—two of them under the shade of trellised vines—, a large circular fountain, and statues, it was described as joyfully crowded and floodlit for two summer months a year, an hour after nightfall.

Naples. Public Gardens and Riviera di Chiaja, Giacomo Brogi, postcard, 19th century.

Naples from the Pier, Antonio Joli, 1762-1777, private collection.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

Gardens

Since classical times, urban gardens have offered promenaders a summer rendezvous, especially in landlocked cities.

The Roman Villa Borghese gardens were already a key urban promenade in the 17th century (Ray 1673, p. 366) and became even more popular either by coach or on foot after their early-19th-century redesign (Baedeker 1869, pp. 111). They lie in the vicinity of the 1st-century-BC Horti Luculliani, a private garden among the earliest and the most beautiful in the city.

The classical Roman tradition of garden promenading underwent a first key revival during the Renaissance and then again during the 18th and 19th centuries. Renaissance pleasure gardens maintained the social and cultural character of the promenade, which offered the possibility that one might interact with or be seen by other courtiers.

Walk at Muro Torto [Pincio], Antonio Puccinelli, 19th century, private collection.

View of Roma with the Pincio Promenade, Anonymous, 19th century,

Bologna, F. Zeri Foundation.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

The garden plays a key role in the work of Boccaccio (2013) as a place to gather, walk and narrate. The Decameron describes, for example, a beautiful garden on the hills around Florence that had wide, straight alleys along which one could walk even under the summer sun, as they were shadowed by grapevines and bushes of jasmine and white roses.

Renaissance Florence also boasted the Boboli Gardens, behind Palazzo Pitti, in which Queen Joanna of Austria, a character from a 16th century book by Girolamo Borro, promenades with her dames to take the air, and which Marie de’ Medici desired to recreate in Paris, eventually inspiring the Luxembourg Garden.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

Gardens for summer promenades were common at the time in many other Renaissance Italian towns.

The Paduan garden of the 17th-century noble knight Bonifacio Papafava, for instance, had ‘Infinite numbers of Cittron and Orange Trees, which forme lovely walks to the Passengers’.

In the same century, Vicenza had the Campo Martio, created in imitation of the Roman garden and where: ‘The Ladies and Gallants resort in the summer Evenings to participate the fresh Ayr, which the surrounding Hills afford’.

Ferrara had the beautiful garden now known as the Montagnola or Montagnone—from a hillock that might date to the 16th century—laid out near Palazzo Belfiore by the ruler of the city, Alberto V d’Este, in 1391.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

Another famous Montagnola is the public garden built in Bologna in 1662 on the site where the Castle of Galliera had stood at the beginning of the previous century. By the early 18th century, it was already the most celebrated promenade of the city, especially in summer, when ‘coaches [ran] back and forth until the dead of the night: & then all coaches stop where they are, to allow taking the air’.

In 19th-century Genoa, the endpoint of the urban promenade became the newly created gardens of Acquasola, which Charles Dickens visited on a midsummer Sunday of 1844, observing how: ‘The Genoese nobility ride round, and round, and round, in state-clothes and coaches at least, if not in absolute wisdom’.

View of the Montagnola in Bologna, Pio Panfili, 1790,

Bologna, Archiginnasio Municipal Library.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

The Villa Reale in Naples, also known as Villa Comunale, became the model for the public gardens that in the 19th and first half of the 20th century were laid out in almost all major towns and cities in the south of Italy and named in its honour.

Specifically designed for promenades and meetings, these gardens became a landmark of town planning and reflected the Enlightenment idea of green space as a healthy social environment, no longer for the exclusive use of the upper classes.

In Calabria, the villa comunale marked the urbanist model that guided the post-1783 earthquake reconstruction of cities and towns such as Reggio, Mileto, Bagnara, Bianco, Palmi and many others; in Puglia, it was a feature of 19th-century urban development; and in Sicily, it also benefitted from another seminal model, i.e. the late-18th-century establishment of the La Flora public gardens in Palermo.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

Bastions and Avenues

Between the mid-18th century and the early decades of the 19th century, relative peace and prosperity—together with Enlightenment concerns for the well-being of the populace and Napoleon Bonaparte’s ambition to establish himself as the ‘legitimate heir of Augustus and Imperial Rome’—enhanced modernising developments in several Italian as well as European cities.

Urban interventions in public spaces—such as the opening of new avenues or the widening of existing ones, the creation of new squares and green areas, and the demolition of city walls—created a climate conducive to the diffusion and intensification of promenading.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

Under Habsburg rule in the second half of the 18th century, the walls of Milan lost their defensive function and were turned by the architect Piermarini into a ‘long and beautiful promenade’, shaded by a double row of horse chestnuts. As a result, the city’s promenade shifted from the Corso di Porta Romana to the stretch of avenue linking Porta Nuova with Porta Orientale (currently Porta Venezia).

The 19th-century conversion of city walls into promenading sites occurred in several other Italian cities, especially in the north and centre. Thus Brescia created a promenade on the walls between Porta San Nazaro and Porta Sant’Alessandro, and between the latter and Porta Torre Lunga, and as early as 1645 the long walls of Lucca had ‘noble and pleasant walks of trees’, and were so wide that in the 1770s ‘the Nobility promenades there by coach’ in summer. A similar green reconversion can still be enjoyed in Parma, on the pentagonal rampart of the 16th-century citadel; in Treviso, on the northern side of the city centre; and in Piacenza, where extant stretches of wall are still surmounted by a garden called the Facsal, after Vauxhall Gardens in London.

View of the Corso on the East Gate's Ramparts in Milano, N. Milini, L. Rados, c. 1820, Milan, Civic Collection of Prints "Achille Bertarelli".

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

The laying out of avenues was a general feature of the urban development of Italian cities in the 18th and 19th centuries, turning existing or newly created streets into popular summer promenades.

In 17th-to-early-19th-century Milan, promenaders used to asolare (‘take the air’) during the hot months along Via Marina, an unpaved avenue that underwent a thorough redevelopment in the 1780s when, to the east of the garden of the late-18th-century Villa Reale, two monasteries were suppressed during Austrian rule and their terrain turned into the city’s public garden by the architect Piermarini. Thus, by spring 1787, the street was lined by two series of five rows of trees—lindens, elms, and horse chestnuts—and flanked by white hawthorn hedges. With this new green aspect, called boschetti (little woods), Via Marina continued to be the corso for the bourgeoise on foot and the nobility in carriages, as it had been in the previous century.

A further two key 19th-century Milanese promenades took place along wide avenues: Corso Loreto (currently Corso Buenos Aires), which was in the middle of two other streets lined with poplar trees, and ‘very frequented by the common folk’; and a stretch of Corso di Porta Romana outside the gate, ‘a beautiful avenue thickly planted with trees, and more than one mile in length without the gate’ that ‘serves, on Sundays, as a promenade for the “folks” living in that quarter of the town’.

THE AL FRESCO PROMENADE

Whether in the city centre or by the seaside, the tree-lined avenue with wide sidewalks featured as a landmark in the planning of Italian colonial cities in the first three decades of the 20th century. A key axis along which to erect the important public and religious buildings, it was specially conceived as the promenade ground of a city and a meeting place to centre the social lives of the colonisers and assimilated natives, in imitation of the customs of the colonial power.

One of the most beautiful examples is found amongst the palm trees and cafés of Asmara’s Harnet Avenue (the former Viale Mussolini), which staged the imported tradition of the evening promenade until the war with Ethiopia in the 1990s and the economic crisis that followed.

In the colonial cities of Eritrea, Ethiopia, Libya, Somalia, Albania, and Greece, the promenade thus became such a fundamental node in social and urban colonial life that even today it affirms the legacy of Italian rule more emphatically than the buildings themselves.