In the world imagery, Venice appears like the witness of a collective past, a place where a lot of individuals and families want to go to, once in life at least. Its appeal is still getting bigger, especially for travellers coming from India, China and Russia. The withdraw of this increasing demand, is that the city is treated like an open-air museum: once arrived, they follow the map of the touristic attractions, looking not only at buildings and monuments but also shops to get a local souvenir as memento of Venice. In general, the touristic interest is to have something that proves they went to Venice rather than experience it.

All these aftermaths confirm what the Situationists thought in the Fifties and Sixties – which will be analysed in the following paragraphs. Venice represents how, in a historical city, the modern capitalistic society is characterised by an organisation of spectacles.

Everybody complains it is impossible to experience real life or actively participate in the construction of the city, as residents are alienated not only from the goods they produce and consume, but also from their own experiences, emotions, creativity and desires.

But what does it mean experiencing a city and what are the tactics to pursue it? An original response was given by Ralph Rumney.

Born in Newcastle-on-Tyne in 1934, Ralph Rumney experienced an unsettled and repressive childhood in Wakefield, prompting him to leave home by stages. His adolescent years were spent lodging with the notorious communist Edward Thompson, hitching to London in 1951 for the Festival of Britain, and then travelling around Cornwall meeting Cornish artists, until, to avoid arrest as a conscientious objector, he moved where the currents brought him, between London, Paris, Milan and eventually settling for a time in Venice.1

Ralph’s life includes drifting in and out these cities, intervals of fame and years of obscurity, and intense contact with fellow artists mixed with times of artistic isolation; let’s say in regard to the art world, visibility and invisibility. After several decades of hiddenness, recently he seems to have become visible again. Few entries regarding him in surveys of British and European art have grown; an exhibition of his work with Lara Vincy coincided the publication of The Consul, an autobiographical memoir edited by Gerdar Berreby in 1999, which was favourably reviewed by the French press, primarily in relation to a rush of publications on Guy Debord. In 2002, the year of Rumney’s death, The Leaning Tower of Venice – a psychogeographic work that will be the focus of this paper – was published by Silverbridge, after 45 years it was completed. This has much to do with the growing fashionability, in artistic, media and academic circles of the Situationist International and their concept of psychogeography, that has become an increasingly common word in the broadsheets as general term of a new interest in urbanism.

The Leaning Tower of Venice is probably his most important work, even if is not so well known. It had quite a complicated development, deeply embedded with Rumney’s personal relationship to Venice and the International Situationists, starting from 1957.

On February he participated as leader of the London Psychogeographical Committee, in the First Exhibition of Psychogeography, presented alongside the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus and the Lettrist International at Taptoe Gallery in Brussels. On the 27th July, eight artists, from these three artistic groups, gathered in Cosio d’Arroscia, a rural town in the north west of Italy. There, Rumney become a founder member – along with Guy Debord, Michèle Bernstein, Walter Olmo and Asger Jorn – of The Internationale Situationniste, a group who would come to be considered one of the most influential artistic factions of the twentieth century.

In Cosio Rumney proposed the psychogeographic exploration of Venice for the first issue of the new born group, planning to de-spectacularize the city by suggesting unknown routes through it, far from Grand Canal. Arguing his choice of the site because ‘Venice like Amsterdam and the Paris of yesteryear offers many possibilities of disorientation. That’s why Debord and Jorn undertook explorations in Paris and Denmark, to unearth the secrets of those urban depths’.2

Venice – where he was already moved and living with Peegen Guggenheim, the daughter of the fabled art collector – lent itself perfectly to psychogeographical exercise due to its labyrinthine nature and the emotional state it provokes.

The work was originally called The Leaning tower of Venice (because of the leaning tower bell in the cover) but then, in November 1957, it was announced in the last number of the newsletter of Internationale Lettriste,3 as Psychogeographic Guide to Venice. The project took the form of a photo story, according to the fotoromanzi format – Italian magazines of photo stories mainly aimed at female readers – by which he got fascinated. At the beginning, the artist wanted to make a film, but owing only a Rolleiflex – a medium format twin lens camera – he was only able to take photographs.

During the development of the project family problems, such as the birth of the son Sandro, occasioned delays on deadline set by Guy Debord, who had already written the preface for the work expected by September 1957. That led to Rumney’s expulsion from the new born group that he founded. This exclusion was announced in the first issue of Internationale Situationniste, in a short text headed Venice Has Conquered Ralph Rumney and the work was no longer published. Nevertheless, in the summer of 1958, Roddy Maud-Roxby, who was the editor of the journal of ARK magazine asked him to provide some material for a publication, which ended up being included a in three different issues. Dueing to Roxby being replaced, Rumney firstly thought that the original material got lost until 1989, when he went to the opening of the situationist exhibition at the Centre Pompidou where he discovered his work was part of the collection of the previous editor. Fortunately, during the exhibition at the I.C.A in London, Rumney commissioned a photographer to shoot The Leaning Tower of Venice. I have personally confirmed with the son of the artist, that the original material is irremediably vanished.

Regardless, the work is documented in three issues of Ark Magazine, a style and design journal created by the students of the Royal College of Art, where they are archived and described below.

An articulated report of the work it is not easy since the author wrote only a few lines throughout the all piece. In addition, all the literature about, is related to the situationist practice, thus there is a lack in publications about how the sequence of shots was designed and pursued. The whole project has 128 shots but only 92 of them were possible to map.

The work published by Silverbridge, which is the only printed publication of Rumney’s work, is in a different order as presented in Ark Magazine. The whole work was subdivided into six documents, each containing a different itinerary. If the editor received the documents as displayed in Silverbridge publication, then I assume he decided to switch the position of document 2 with 5 for two reasons. First, the document 5 illustrate the consequential itinerary after the one in document 1; secondly, since it shows a key feature of the study, it was needed in the front page. Consequently, if we rely on Silverbridge’s photographs of the original project, it means that the primary sequence was different than the one issued by Ark Magazine. It leads that Document 1, is followed by document 5, followed by 3, 4, 5 and finally 6. Both the sequences start from Piazzale Roma and end in Rialto.

The first two documents were issued in Ark No 24, published in spring 1958. The Leaning Tower of Venice compared under the section ‘environment’, after Smith and Denny’s Project for a Film: Ev’ry-Which-Way, arranged on the recto side of a large pull-out length of pages in the middle of the issue. Smith and Denny’s collaged storyboard, itself a built environment of billboards, slogans, faces of the cinema screen and their own typewritten or handwritten reflections, offers a viewpoint which pans over the world. (Fig. 1)

The ‘intermittent stimuli’ of the urban environment ‘make montage’ in their relation of ‘private (painter) situation to a public world, in which it is ‘fruitless to search for universals’.4 The concertina fold out is too wide to view in respect to all its aspects, much like the experience of viewing on of large-scale paintings for which Denny and Smiths were becoming known or the widescreen of the cinema.

The act of viewing is both one of attempting to assimilate the overall ‘flux’ of images of headlines, while attempting to make sense of given points across the field of visual register: headline, faces, monoprints of found photographs.

The decision to showcase this work and the Leaning Tower of Venice in the same page is therefore appropriate as Rumney’s work can be read as a flux of images as well. Every shot pinpoint certain element in a related environment which provoke a particular pattern of responder to the reader. This can be proven by looking at the front page of the work.

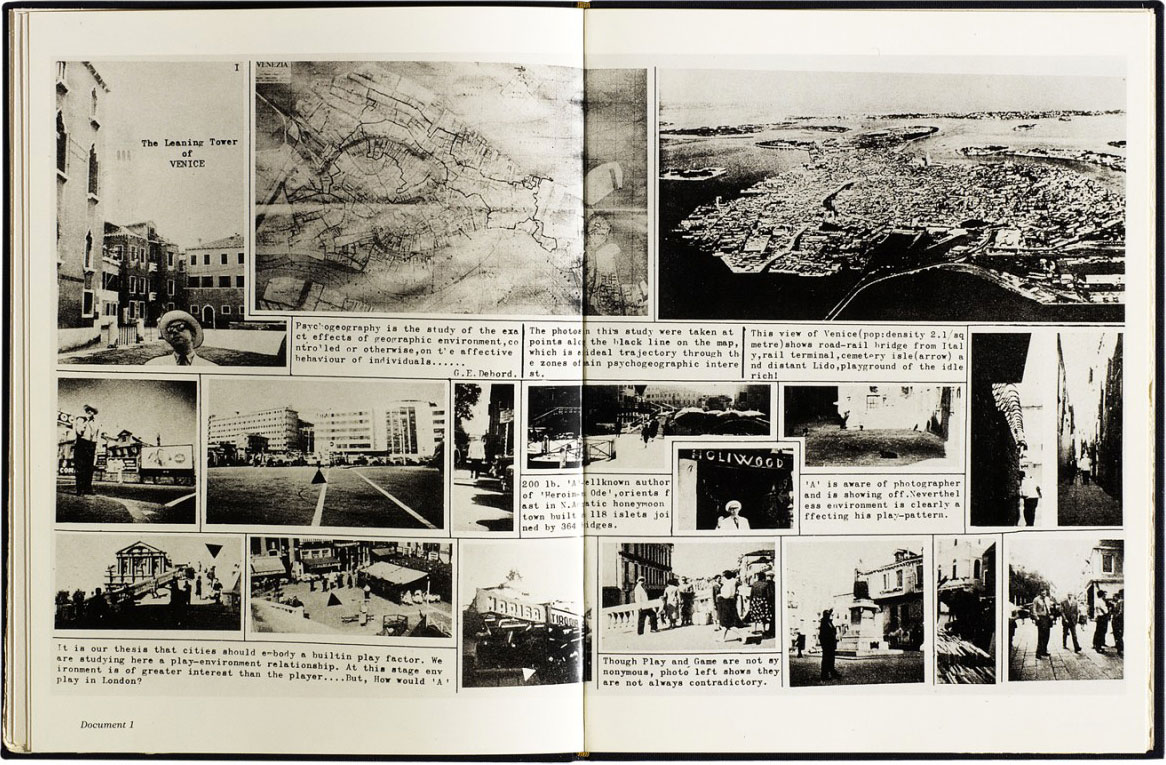

As in every research, at the beginning three key features of the program of the study are presented: theoretical background, location and protagonist. (Fig. 2)

Fig. 1 Smith and Denny, Project for a Film: Ev’ry-Which-Way in Ark Magazine No. 24.

Fig. 2 Cover page of The Leaning Tower of Venice in Ark Magazine No. 24.

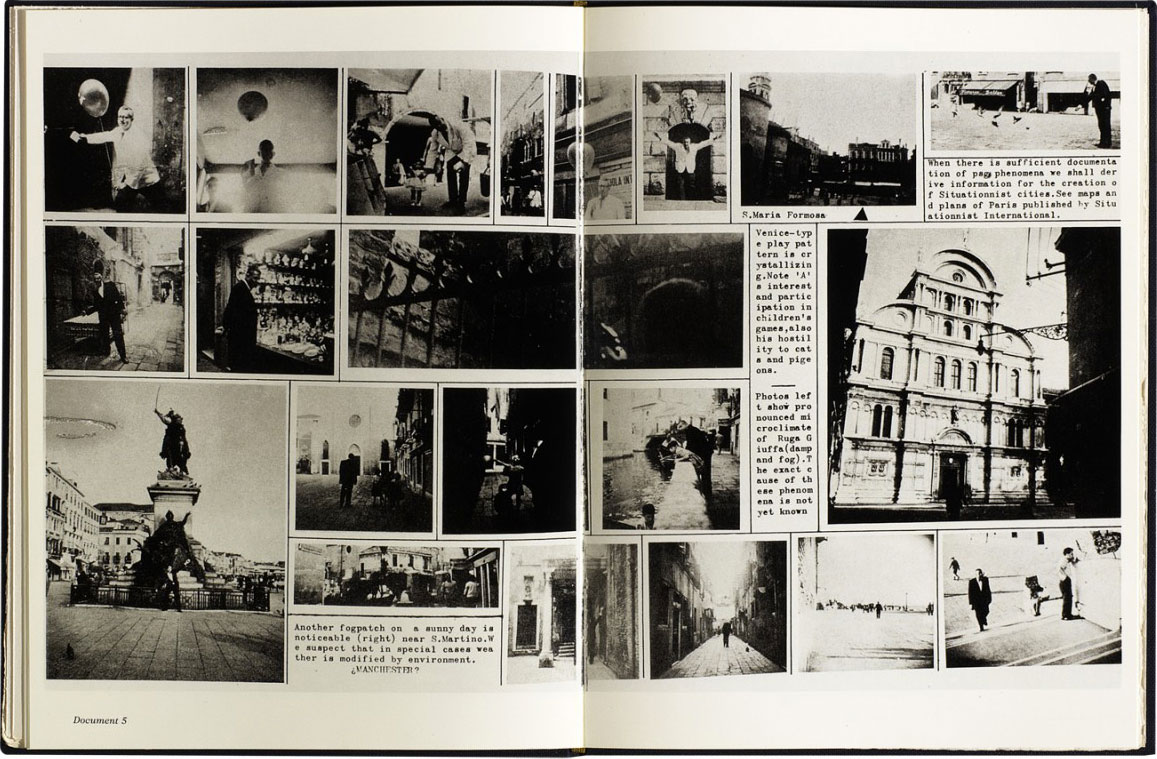

Fig. 3 The beginning of the derive. First

itinerary: Piazzale Roma, Ponte degli Scalzi, Strada Nuova, Campo Santi Apostoli.

Fig. 4 Second itinerary. Campo Santi Apostoli, Campo Santa Maria Formosa, Campo Bandiera e Moro, Riva Ca’ di Dio.

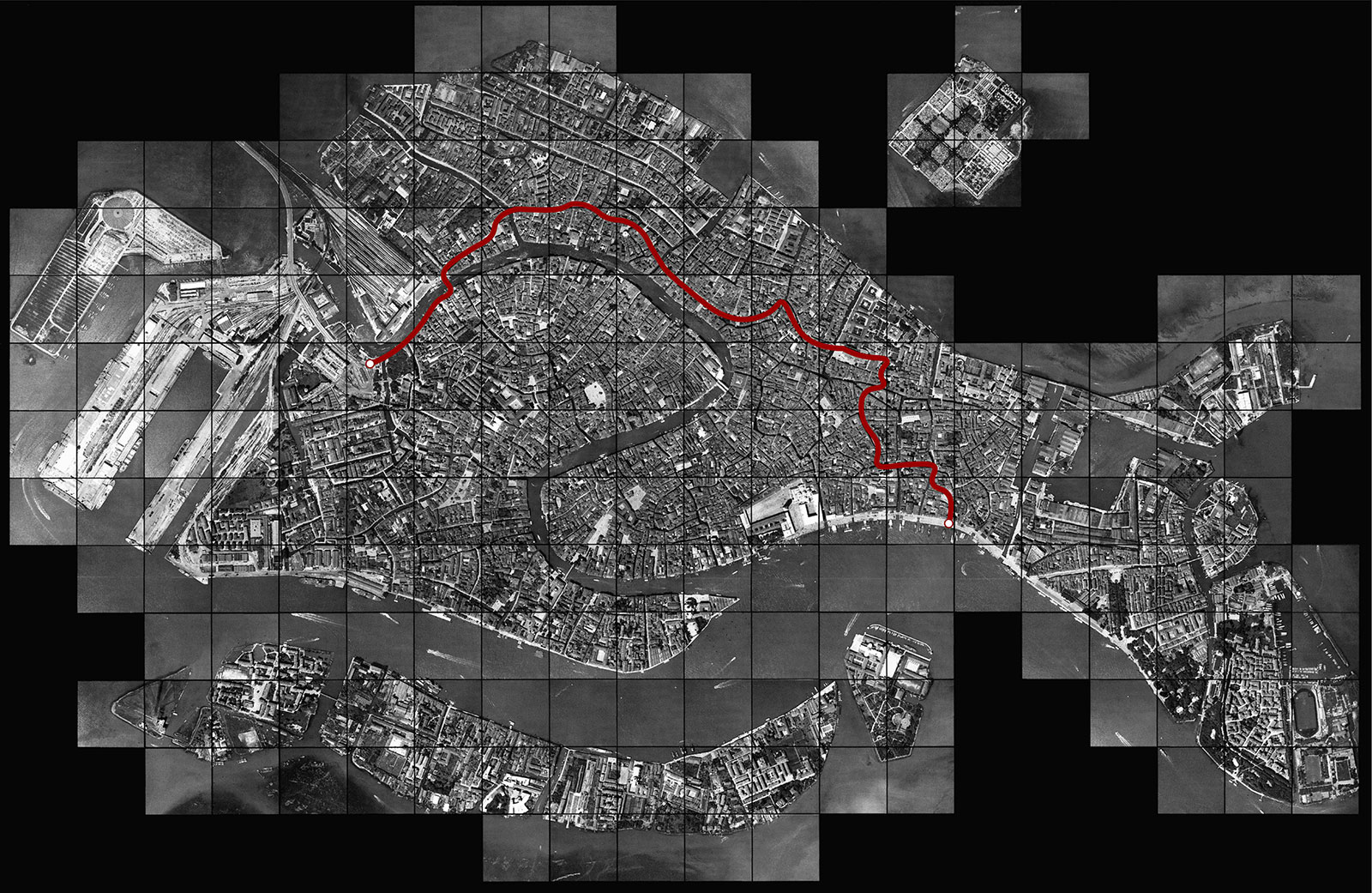

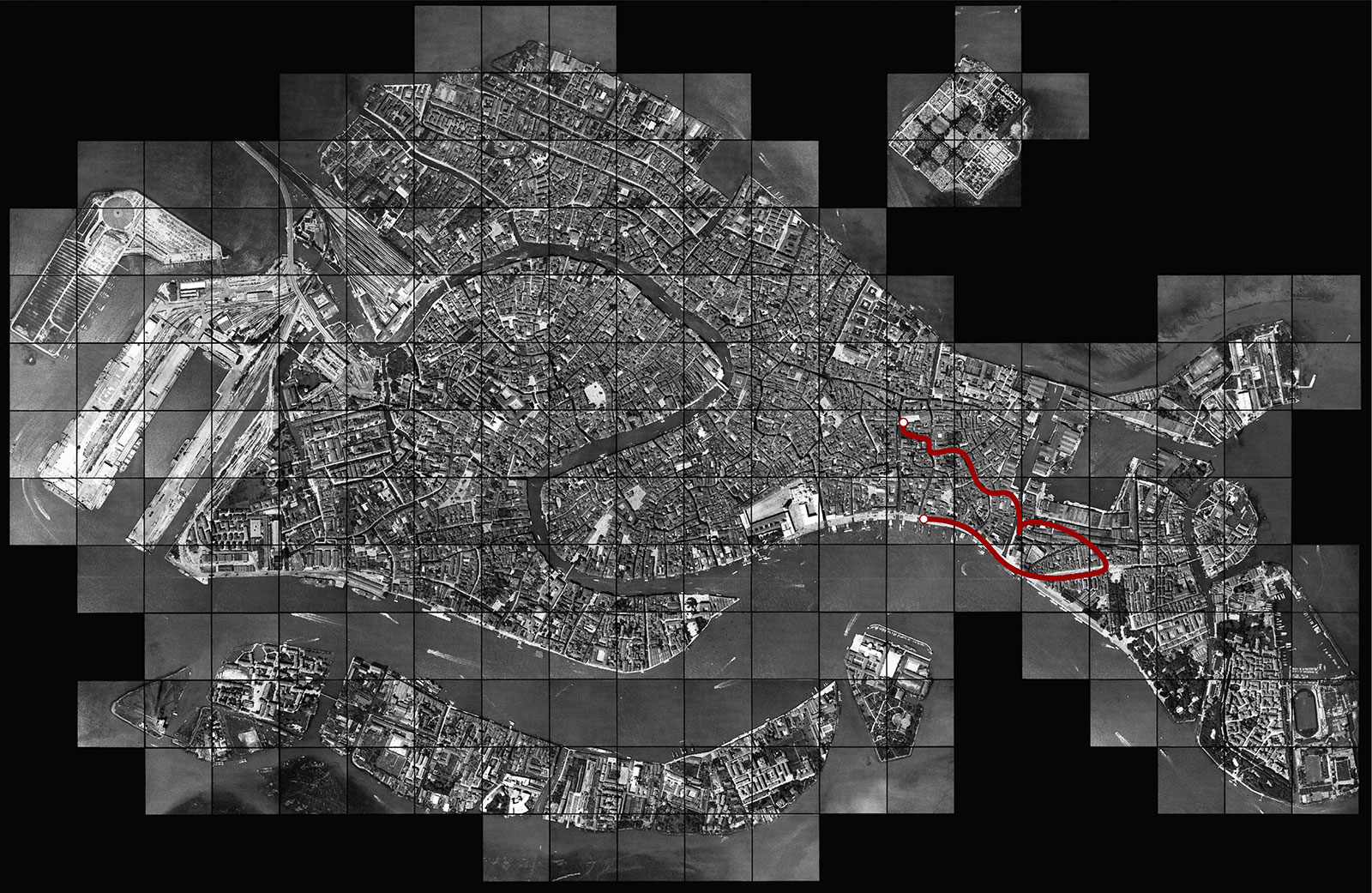

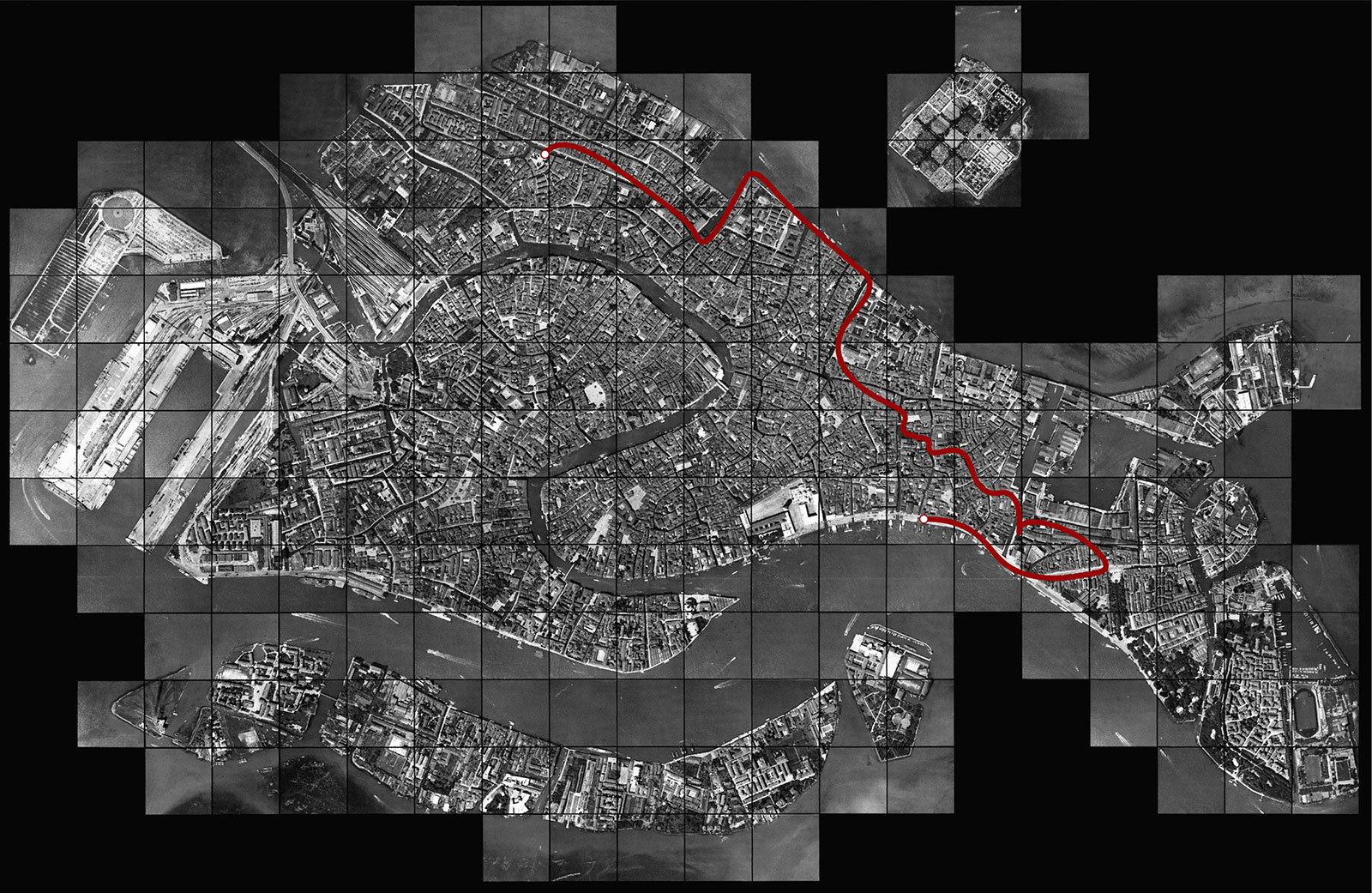

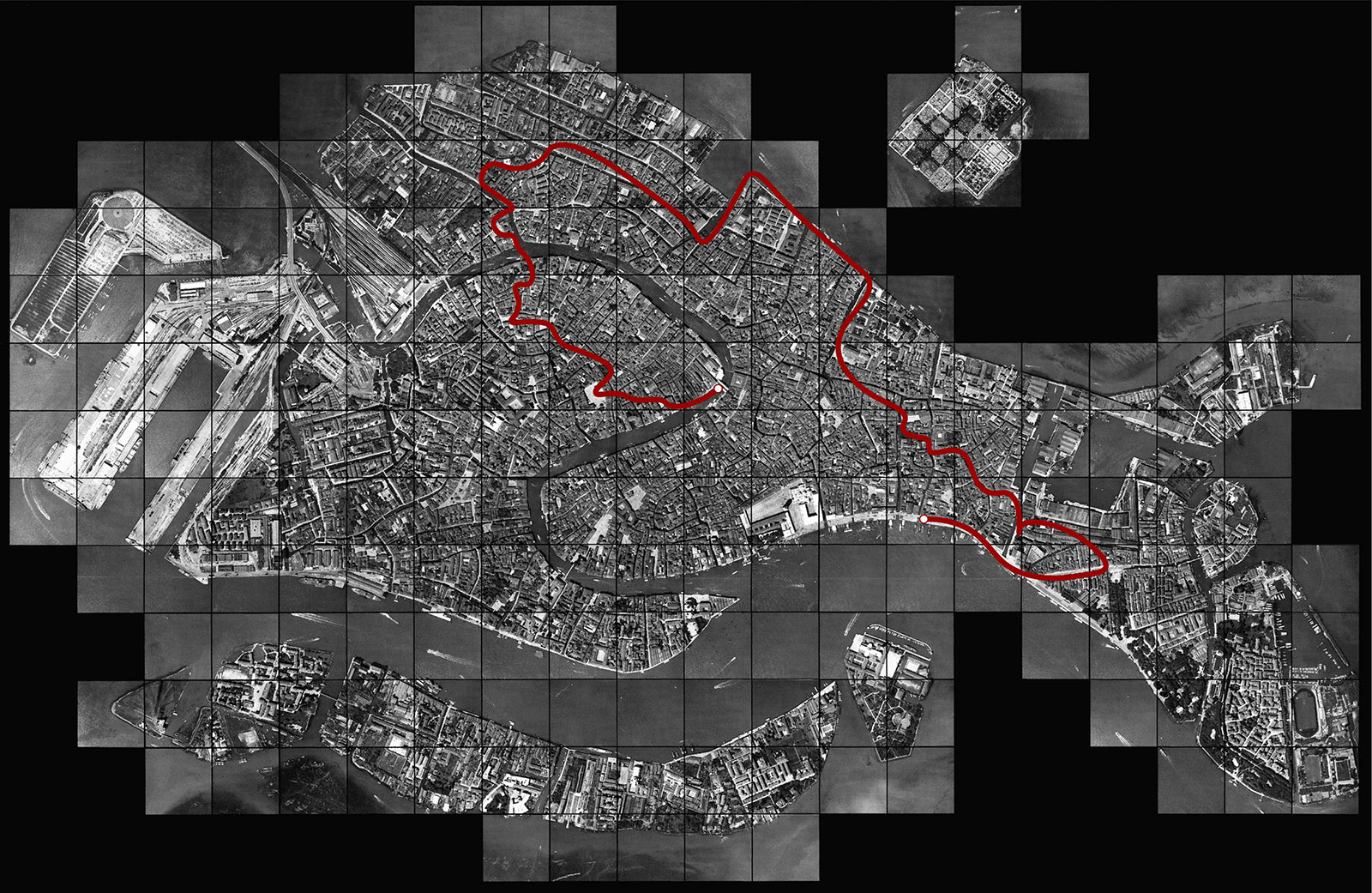

Fig. 5 First and Second itineraries from aeral view.

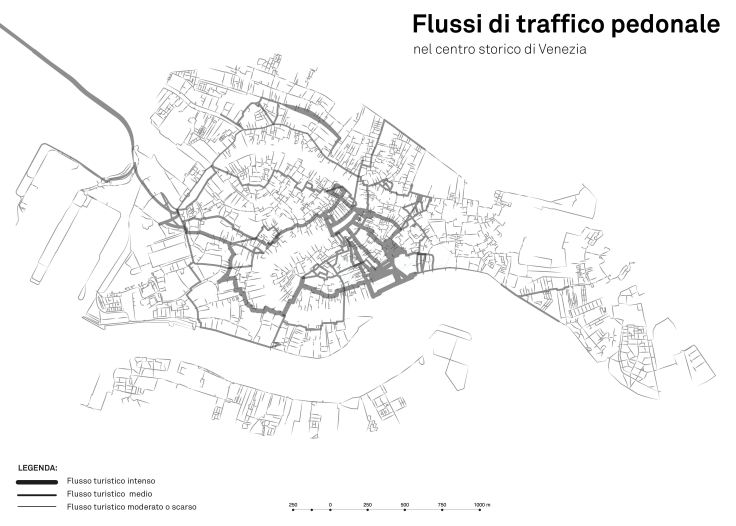

Fig. 6 Touristic pedestrian flux in Venice.

The first typewritten text is a quotation of Guy Debord’s definition of Psychogeography as the ‘study of the exact effects of geographic environment, controlled or otherwise on the affective behaviour of individuals’.5 It follows a small reproduction of a map of Venice, pasted at the top of page, upon which a long black line snakes through the narrow alleyways and water channels, drawing an ideal trajectory through the zones of main psychogeographic interest. On the right, a bird-eye view of the city is added to show better the railway connection to the island. On the bottom, the Protagonist of the story, the American Beat writer Allan Alsen (alias ‘A’) is presented as a player. This ‘study’, rather than taking the city itself as its focus, pays greater attention to the ways in which the environment affects the experiential ‘play-pattern’ of the ‘player’.6 What Rumney did not declare in this document is the ludic act that Alsen is doing: the dérive. It is a form of remapping the city, which will be better explained later, based on a performative practice of walking without functional aim, yet walking creatively. Furthermore, a poem of Alsen, The Easiest Room in Hell,7 is included in the same issue, following Rumney’s work. (Fig. 3)

The first picture of the protagonist is shot at Piazzale Roma, where the drift begins. This route – Piazzale Roma, Ponte degli Scalzi, Strada Nuova, Campo Santi Apostoli– is the most direct way to enter the core of the city when the traveller arrives by vehicle or train. Nowadays it is one of the most congestioned routes, as it shown in Fig. 6. Some of the photographs are overlaid with a small black or white triangle that –mirroring Alsen’s alternating black-and-white jacket and trouser combination – points out ‘A’.

On the other half of the page (Fig. 4), the second sequence starts with the poet larking around with a big balloon on a string, feeding pigeons and joining children’s street games. This itinerary chosen by the author was characterised by residential neighbourhoods which still exist but in a minor proportion than 50 years ago. The last two typewriting deals with the microclimate in the two calle – Venetian term for narrow street. Despite it is a sunny summer day there is a fogpatch that Rumney suggests it might be a product of the environment. His intuition is right, during the summer the air in a few spots of Venice gets quite stiff due to high umidity and lack of air circulations. Campo S. Martino, where the two characters noticed it, is indeed totally embedded between buildings and really narrow streets.

The next two documents are published in the following Ark No 25, the last issue edited by Roxby. Prior to these, a dialogue between Rumney and Alsen about the Beat generation.8

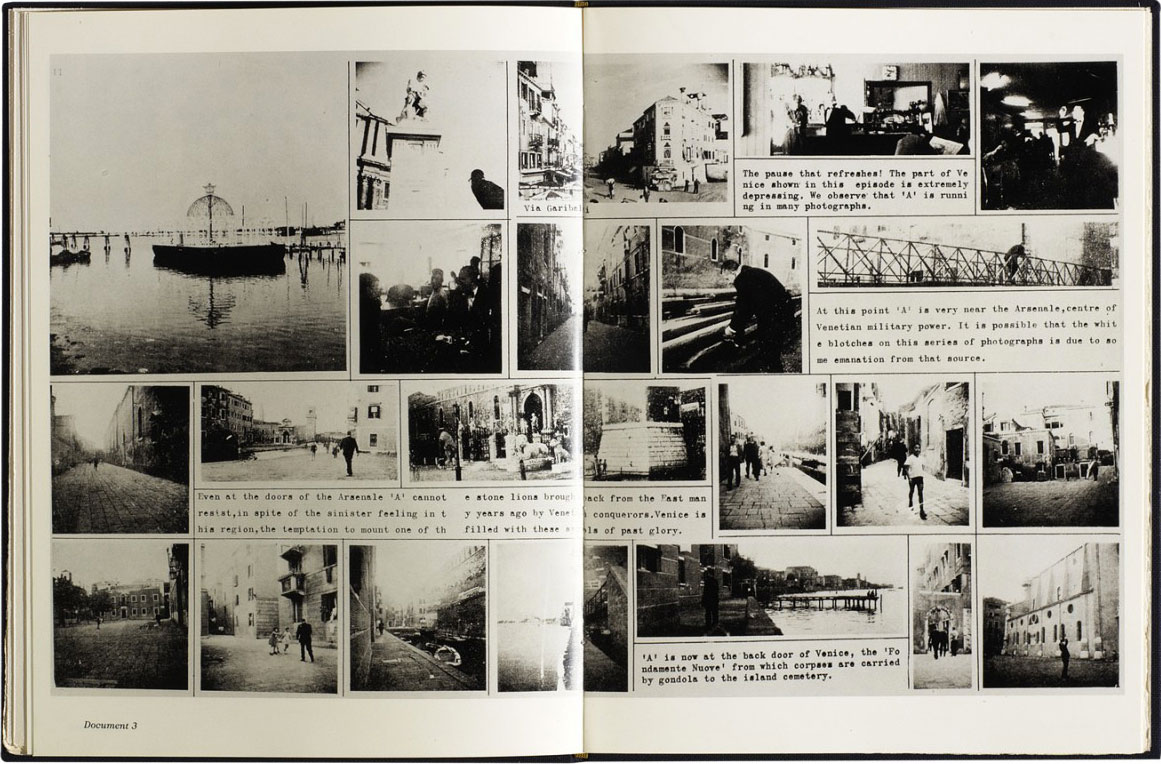

Alsen and Rumney are now vertically crossing the sestiere called Castello which they define as ‘depressing’ (Fig. 7-8) Starting from the bottom – Riva Ca’ Dio – they move towards the norther fringe of Venice, where they face few islands like the cemetery of S. Michele, established during the Napoleon era. Few lines describe the places to give a brief historical and functional context to the reader. The author and Alsen probably perceived this area depressing for the lack of human interaction. As it shown in the pictures, there are not so many people around. This area is also nowadays merely residential and unspoiled by the tourism – except for Via Garibaldi that gets a bit busier during the opening of the biennale but during the rest of year is quiet. Furthermore, since it is the most labyrinthine part of the city due to the height of the buildings and the lack of campi (little squares), walking around might be quite sinister.

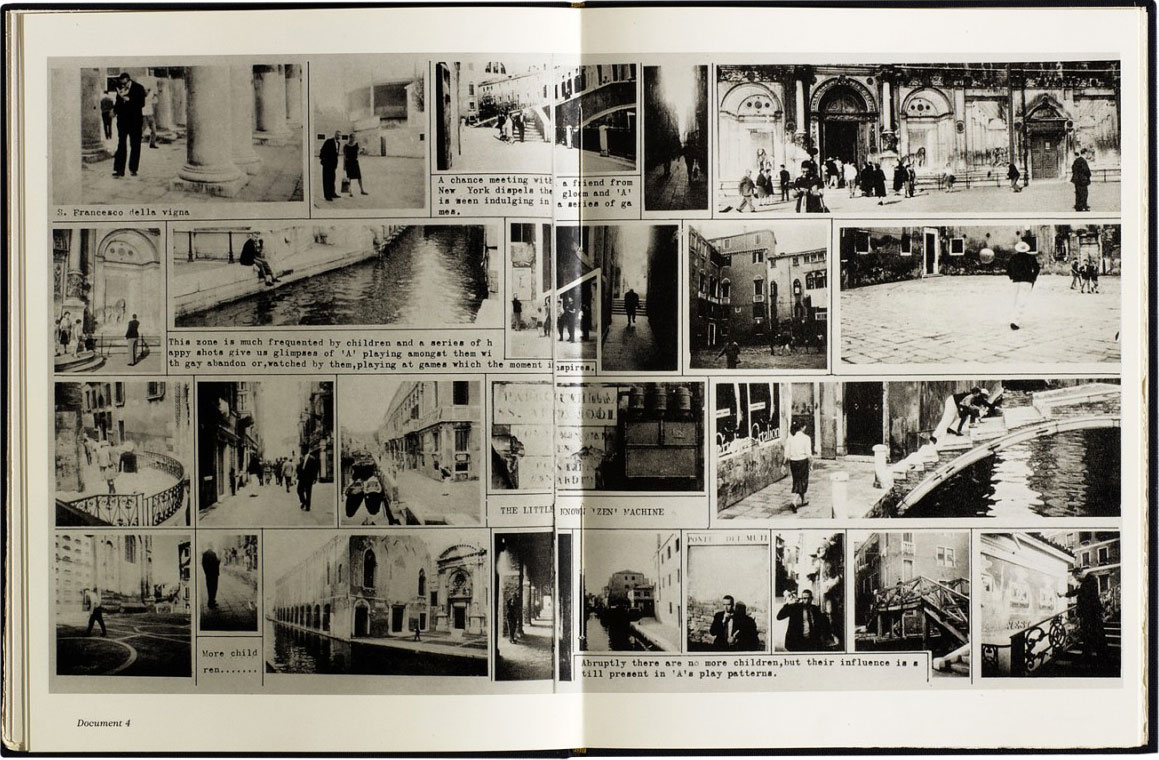

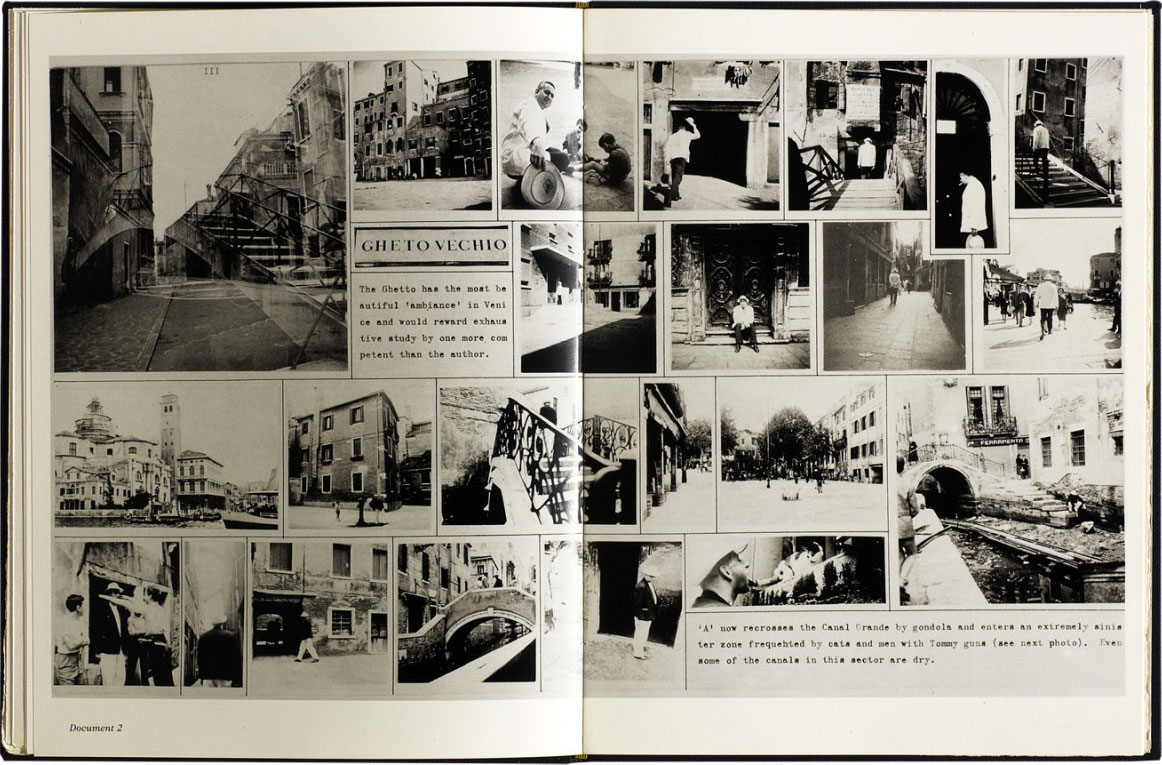

The journey continues from Campo S. Francesco della Vigna towards Gheto Novo (Fig. 9-10). This route connects the two northern sestieri, from eastern Castello to western Canarareggio. As the walk continues towards the Ghetto ‘abruptly there are no more children’ but it is evident ‘their [children] influence is still present in Alan’s play patterns’9 which you can see in the shots showing ‘A’ in the mute’s bridge mocking the silent gesture. Currently this area is still pretty much as Rumney depicted, not so entangles by tourist except for Riva della Misericordia – now popular for a cluster of bars. The presence of children is strong as there are many kindergartens and primary schools nearby. Finally, the third part of the project was published as an insert or Ark 26, edited by Ken Baynes.

Fig. 7 Third itinerary. Riva Ca’ di Dio, Via Garibaldi, Arsenale, Celestia, Campo San Francesco della Vigna.

Fig. 8 Third itinerary from aeral view.

Fig. 9 Fourth itinerary. Riva Ca’ di Dio, Via Garibaldi, Arsenale, Celestia, Campo San Francesco della Vigna.

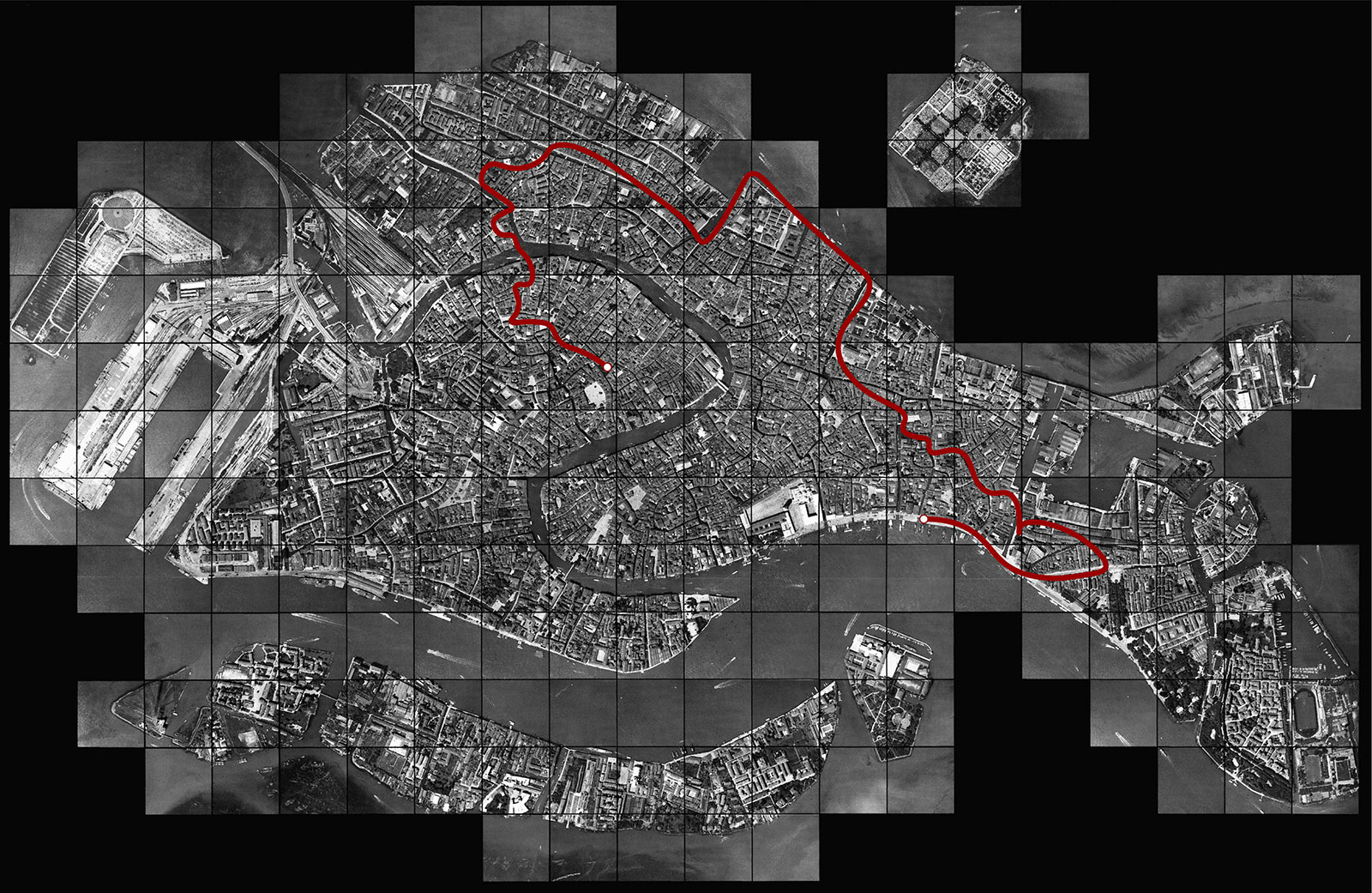

Fig. 10 Third and Fourth itinerary from aeral view.

Fig. 11 Fifth itinerary. Gheto, San Giacomo dell’Orio, Ponte delle Tette.

Fig. 12 Third, Fourth and Fifth itineraries from aeral view.

Fig. 13 Sixth itinerary. Ponte delle Tette, Campo San Polo, Rialto.

Fig. 14 Third, Fourth, Fifth and Sixth itineraries from aeral view.

Proceeding from the Gheto southwards, the fifth itinerary (Fig. 11-12) Gheto, San Giacomo dell’orio, ponte delle tette), is described as ‘the most beautiful ambience in Venice’. The document opens with a photomontage of an overlapping bridge that crosses to the campo, ending in a wall. From this calm environment, Alsen moves to an ‘extremely sinister zone frequented by cats’10 traversing the Canal by gondola. It is understandable for Rumney to think this zone as sinister: before the early 2000, this area was characterised by being dangerous and aesthetically poor.

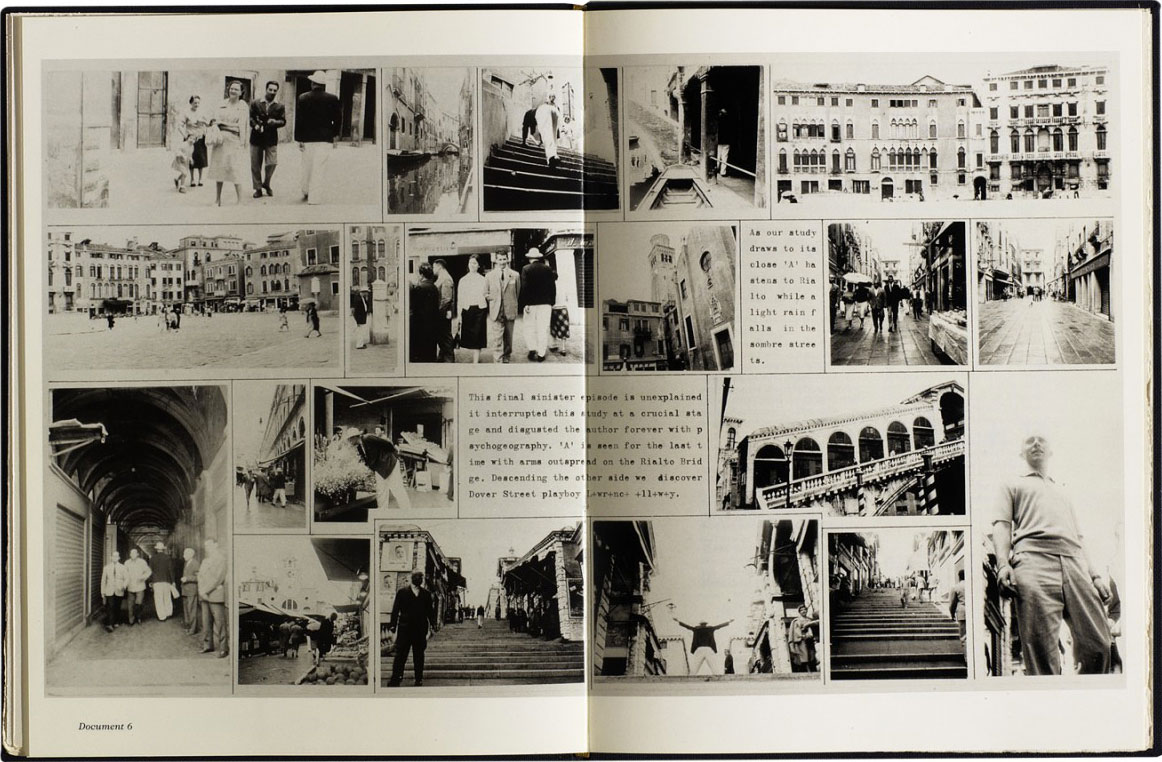

The sixth and final journey, starting from Ponte delle Tette and ending in Rialto bridge (Fig. 13-14), is the epilogue of the photo essay. This makes the study look unfinished since the former trajectory on the map is much extensive.

From the central typewrite it is clear the protagonist, ultimately ends up being Rumney himself as author/artist, and not Alan Alsen as initially thought – who disappears over the brow of the Rialto Bridge, never to be seen again.11 A picture of him with arms outspread on the top of rialto bridge leads to a mysterious line which concludes the project: ‘Descending the other side we discover Dover Street playboy L+wr+nc+ +ll+w+y’.12 These letters represent a character who is probably Lawrence Alloway, art critic and leader of the Independent Group, which gets connected by Rumney to Jorn’s Situationist International.

It might be that this unexpected ending affected even more the critique Guy Debord wrote in the first issue of Internationale Situationists. Nevertheless, the preface Debord created in September for the expected publication of The Psychogeographical guide of Venice was actually positive. He described it as ‘the first exhaustive psychogeographical work applied to urbanism’,13 endorsing Rumney’s choice of Venice among other zone of experimentation because of the ‘sentimental resonance of the town that is tied to the most backward emotions of the old aesthetic’.14

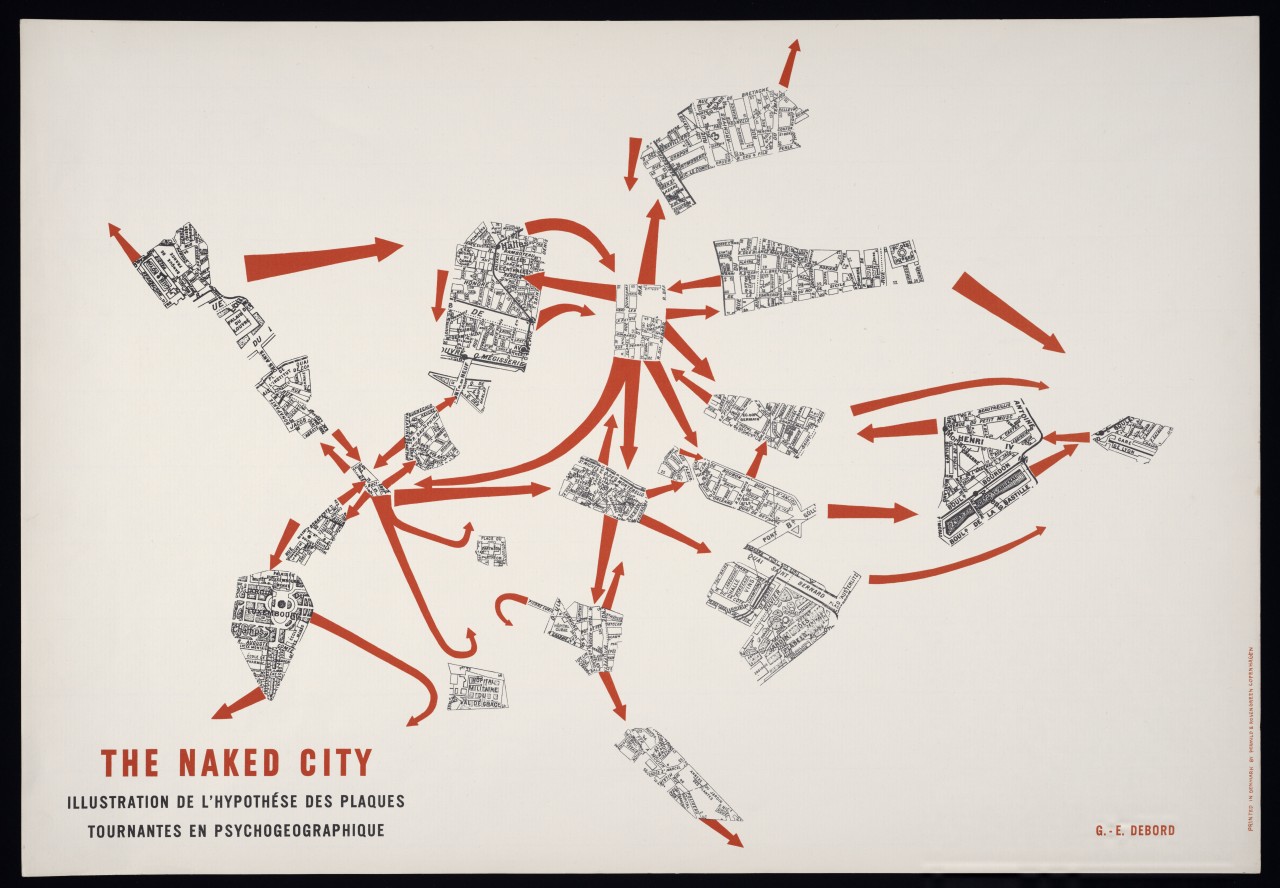

Debord seems admitting Rumney overtook his experiment conducted in Paris in the same year, The Naked City that, as McDonough said, acted as a statement of the future direction to be explored in following years by the group, regarding the construction and perception of urban space.

In the preface, Debord reiterates few points already presented in the Society of the Spectacle, arguing that under advanced capitalism ‘everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation’.15 As LeFebvre also stated, the social space once directly lived had now moved into an abstract one, which matches Debord’s view. The goal of the Situationists was to explore the space of the modern city with all of its contradictions, hidden under an apparent homogenizing capitalistic ideology. Their objective is to retreat the capitalistic representation and perception of the city with a new tactic representation tool, known as psychogeographical map.

Pursuing a deconstructive analysis of the representation of the city in a map, as the Plan de Paris, brings to light the ideology that Debord wanted to contrast. Capitalistic powers are implicitly presupposed on a traditional map. These powers are staged by what Marin defined as Eidetic profile16 of city: in the viewer’s memory a city is recorder in reference of certain urban objects that stand for the whole town. These are Eidetic operators within maps that represent power structures. For instance, The Plan de Paris, the Hausmannized Paris, reveals the discourses made by these operators. It is a homogenized and plain view, but actually hides a previous production of distinctions and differences that has led the city to look as it currently does.

Modernization had evicted the working class from its traditional quarters in the city centre and then segregated the city along lines. Thus, masking the successive nature developed in time, traditional plans are structured in a “description” mode of discourse, as they show the city as an account of ‘the knowledge of an order of the places’.17

On the other side of the spectrum, Debord stands with his The Naked City (Fig. 15). He looks at the urban space from diffused sights, sought by different movements around his new defined quarters called units of atmosphere. In and out them, the red ink arrows pinpoint the derive as a pedestrian speech, that acts to rei1nstate the value of space in a society that privileges trade.

The arrows cross also white blanks of space through which Debord is making segments of Paris disappear, since they never even existed in the first place. For that reason, and for showing diachronical movements that a walker takes around the psychogeographic hubs, his map is actually not a description but rather a narrative around the city.

Based on this, Rumney made this narrative more accessible to the viewer. Even though his work is visually not a map, it shows more effectively both the spatial and the emotional narrative from one place to another, as he records the walker during his psychological reaction to each hub.

Debord and Rumney share the same tactic – the derive – that destructs normative behavings in order to ‘begin to grasp our positioning as individual and collective subjects and regain a capacity to act and struggle which is at present neutralized by our spatial as well our social confusion’.18

Rumney succeeded in establishing the basic elements of a map of Venice in which the notational technique plainly surpasses all previous psychogeographic cartography even if as the author said, ‘we should not forget Ivan Chtcheglov was the real inventor of psychogeography’.19

In addition, the tactic of the derive as act of re-appropriation of the public space, restoration of the city’s fullness, richness and history seems to be more actual than ever. With the advent of the spectacle culture, the history of the city is put back into play as a harmless form of entertainment for tourist attractions, where public space is commodified for very private consumption. And, if Debord declares, the museumization of Paris is the prime example of this process, then Venice is its paramount. A city in which the political organisation – external to the daily activity of the citizens and to their attachment to the places they live in – has submitted it to the norms of an abstract space – like the open-air museum that show the realm of myth. The Leaning Tower of Venice, even if it was conducted in the 50s when the city just started being inexorably mediated by the spectacle of the tourist experience, appears to be a resourceful work, despite the critiques it has received.

According to Simon Sadler, ‘Rumney’s montage ultimately fails because its creator cannot make up his mind whether the point of his work is the demonstration of a systematic attempt to map play at work or to be playful in its own right: it failed to yield anything remotely like “data”, its author struggling to explain the significance of his encounters with children and old acquaintances, account for the romance of Venice, and identify “sinister”, “depressing” and “beautiful” zones’.20

This critique it’s partly true as Rumney does not provide a numbered urban database of Venice. But on his defence, he declared from the beginning the focus of the study ‘was play-environment relationship since the thesis was that all the cities should embody a built-in play factor’.21 Consequently, the encounters with children are not meaningless but on the contrary are exactly what Rumney was looking for. The derive – that is a ludic act – undertaken was meant to find other uses for space besides the predefined and functional ones, to find the spirit of the place (genius loci) physically manifested in the street’s architecture and the containing environment.

Regardless, Rumney, as he explained in The Consul, tried to send The Leaning Tower of Venice in time for it to appear in the journal but the original document only reached Impasse de Clairvaux where Debord lived 2 months after it came out.

The response of Debord was harsh: he officialized Rumney’s expulsion from the group in his article in the first issue of the SI’s new journal, Internationale situationniste. Publishing a couple of mug-shots, he argues that ‘the Venetian jungle has shown itself to be the stronger, closing over a young man full of life and promise’.22 By saying this Debord is ironically deeming Rumney to have been affected psychically by his geographical surroundings to the point of losing sight of the seriousness of his endeavour. He considered the excuse of the birth of a child as foolish that since a true revolutionary should not distract from his path. Rumney did not take exclusion easily and later he admitted it left him very demoralized, although he also realized his own responsibilities: ‘I recall having said in Cosio that any lack of the fanaticism necessary for our advancement must be punished by expulsion’.23

The following years were really complicated for Rumney. In 1967 his wife Pegeen died of an overdose of sleeping tablets and whiskey, and her mother tried to have Rumney arrested for murder and failing to assist a person in danger. Partly to escape her attention Rumney sought refuge at Félix Guattari’s clinic at La Borde. Only after he was assured there were no grounds for his prosecution did he leave Paris. In 1970 he returned to London and worked as a broadcaster on the radio station ORTF. While in Paris at a gallery party he bumped into Michèle Bernstein, the first wife of Guy Debord. They resumed their friendship and married couple of year later. Rumney died of cancer after a long illness in March 2002.

Overall, The Leaning Tower of Venice offers a valuable insight of the city, that has now slipped far down the greasy gondola pole of selling out to tourism. But, as Rumney showed following the derive of Alsen, a drifter would not be attracted by constructed touristic selling spots. On the contrary, he would discover an alternative Venice – not San Marco, not the Rialto Bridge. The importance of a sense of self-consciousness of existence within a particular environment or ambience, described by Sartre as ‘situation’ seems to be needed not only for tourists but also for residents. Linked to his theories about freedom of choice and responsibility, the new “science of situations” expounded by Debord entailed not the passive acceptance but the active creation of these situations. Venice needs real collective action to prevent to be irremediably overwhelmed by daily cannibal visitors. And the derive practice could be a tactic to consider. As the situationists in the Sixties, we now have to collectively work towards using all means of revolutionizing everyday life. We need to construct new ambiences that will be both the products and the instruments of new behaviour to the city. To do this, we must from the beginning make practical use of the everyday processes and cultural forms that now exist, while refusing to acknowledge any inherent value they may claim to have. To study and learn from the lessons of the SI is no idle pastime or exercise in passive contemplation. It is nothing if not a determined step towards the realization of a future society where the SI’s ideas about an useful life are no longer quite so exceptional.

Fig. 15 Guy Debord, The Naked City, 1958.

Fig. 16 Cosio d’Arroscia, Italy, 1957. From left to right: Pinot-Gallizio, Piero Simondo, Elena Verrone, Michèle Bernstein, Guy

Debord, Asger Jorn, Waltern Olmo. Ralph Rumney took the picture.

1. Rumney, Ralph, The Consul, London, Verso, 2002, p. 11.

2. Ibid., p. 47.

3. Potlatch, 29, 1957.

4 Denny, Robyn; Smith, Richard, ‘Ev’ry Which Way’, ARK, 24, 1959, p. v.

5 Rumney, Ralph, ‘The Leaning Tower of Venice’, ARK, 24, 1959, p. vi.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid., p. x.

8 Alsen, Alan, ‘The Easiest Room in Hell’, ARK, 25, 1960, p. 26.

9 ARK, 25, 1960, Royal College of Art, London, p. 32.

10 Ibid., p. 26.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid.

13 Rumney, Ralph, The Consul, op. cit., p. 53.

14 Ibid.

15 Debord, Guy, Society of the Spectacle, Detroit, Black &Red, 1977, p. 1.

16 Marin, Louis, ‘The City in its Maps and Portraits’, in Louis Marin, On Representation, Stanford (Calif.), 2001, p. 211.

17 McDonough, Thomas, ‘Situationist Space’, October 67, 1994, p. 65.

18 Jameson, Fredric, Postmodernism or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, London, Verso, p. 92.

19 Rumney, Ralph, The Consul, op. cit., p. 43.

20 Sadler, Simon, The Situationist City, Cambridge (Mass.), MIT Press, 1998.

21 Rumney, Ralph, ‘The Leaning Tower of Venice’, op. cit., p. vi.

22 Rumney, Ralph, The Consul, op. cit., p. 54.

23 Ibid., p. 55.

Situationist International Online: http:// www.cddc.vt.edu/ sionline

Debordiana: http:// www.chez.com/ debordiana

The Leaning Tower of Venice, Silverbridge – also for images http://www.royalbooklodge.com/en/publications/the-leaning-tower-of-venice/

The Leaning Tower of Venice, mapping the journey http://www.museodelcamminare.org/progetti/re_iter/rumney/rumney.html

Cover page: Rumney, Ralph, Untitled (detail), Oil on board 77 x 64cm (30 5/16 x 25 3/16in), Collection of Frank Avray Wilson.

Fig. 1 Delmonte, Irma, Smith and Denny, ‘Project for a Film: Ev’ry-Which-Way’, Ark Magazine, 24, 1959.

Fig. 2 Delmonte, Irma, Cover Page, ‘The Leaning Tower of Venice’, Ark Magazine, 24, 1959.

Fig. 3 Rumney, Ralph, ‘Document 1’, in The Leaning Tower of Venice, Paris, Silverbridge, 2002.

Fig. 4 Rumney, Ralph, ‘Document 5’, in The Leaning Tower of Venice, Paris, op. cit.

Fig. 5 Delmonte, Irma, Mapping Ralph Rumney’s itinerary on Venice fotopiano, 2019.Fig. 6 Flussi pedonali nel centro storico di Venezia, https://occupysantamarta.wordpress.com/2018/09/27/mapping/

Fig. 7 Rumney, Ralph, ‘Document 3’, in The Leaning Tower of Venice, Paris, op. cit.

Fig. 8 Delmonte, Irma, Mapping Ralph Rumney’s itinerary on Venice fotopiano, 2019.

Fig. 9 Rumney, Ralph, ‘Document 4’, in The Leaning Tower of Venice, Paris, op. cit.

Fig. 10 Delmonte, Irma, Mapping Ralph Rumney’s itinerary on Venice fotopiano, 2019.

Fig. 11 Rumney, Ralph, ‘Document 5’, in The Leaning Tower of Venice, Paris, op. cit.

Fig. 12 Delmonte, Irma, Mapping Ralph Rumney’s itinerary on Venice fotopiano, 2019.

Fig. 13 Rumney, Ralph, ‘Document 6’, in The Leaning Tower of Venice, op. cit.

Fig. 14 Delmonte, Irma, Mapping Ralph Rumney’s itinerary on Venice fotopiano, 2019.

Fig. 15 Debord, Guy, The Naked City, 1958, in Simon Ford, The Situationist International: A User’s Guide, London, Black Dog, 2005.

Fig. 16 Rumney, Ralph, 1957, in Simon Ford, op. cit.

© Irma Delmonte 2019, licensed under Creative Commons CC BY-NC-ND 4.0